- Home

- Mark Feldstein

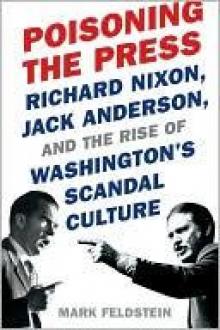

Poisoning The Press

Poisoning The Press Read online

POISONING THE PRESS

POISONING THE PRESS

RICHARD NIXON, JACK ANDERSON, AND THE RISE OF WASHINGTON’S SCANDAL CULTURE

MARK FELDSTEIN

FARRAR, STRAUS AND GIROUX NEW YORK

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

18 West 18th Street, New York 10011

Copyright © 2010 by Mark Feldstein

All rights reserved

Distributed in Canada by D&M Publishers, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2010

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Feldstein, Mark Avrom.

Poisoning the press : Richard Nixon, Jack Anderson, and the rise of Washington’s scandal culture / Mark Feldstein. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-374-23530-7

1. Nixon, Richard M. (Richard Milhous), 1913–1994—Relations with journalists. 2. Anderson, Jack, 1922–2005. 3. Press and politics United States—History—20th century. 4. Presidents—United States—Press coverage—Case studies. 5. United States—Politics and government—1969–1974. 6. Political corruption—United States—History— 20th century. 7. Political culture—United States—History—20th century. 8. Political culture—Washington (D.C.)—History—20th century. 9. Presidents—United States—Biography. 10. Journalists—United States—Biography. I. Title.

E856.F45 2010

973.924092—dc22

2010010272

Designed by Jonathan D. Lippincott

www.fsgbooks.com

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For Beth and Robbie,

my unconditional pride

and everlasting joy

One day we’ll get them—we’ll get them on the ground where we want them. And we’ll stick our heels in, step on them hard, and twist.

—Richard Nixon

Nothing produces such exhilaration, zest for daily life, and all-around gratification as a protracted, ugly, bitter-end vendetta that rages for years and exhausts both sides, often bringing one to ruin.

—Jack Anderson

CONTENTS

Prologue

Part I: Beginnings

1. The Quaker and the Mormon

Part II: Rise to Power

2. Washington Whirl

3. Bugging and Burglary

4. Comeback

Part III: Power

5. The President and the Columnist

6. Revenge

7. Vietnam

8. The Anderson Papers

9. Sex, Spies, Blackmail

10. Cat and Mouse

11. Brothers

12. “Destroy This”

13. From Burlesque to Grotesque

14. “Kill Him”

15. Watergate

16. Disgrace

Part IV: Endings

17. Final Years

Epilogue

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

Index

POISONING THE PRESS

PROLOGUE

It seemed an unlikely spot to plan an assassination. After all, the Hay-Adams was once one of Washington’s most venerable old mansions, adorned with plush leather chairs, rich walnut paneling, and ornate oil paintings, located on Lafayette Square directly across the street from the White House. But on a chilly afternoon in March 1972, in one of the most bizarre and overlooked chapters of American political history, the luxury hotel did indeed serve as a launching pad for a murder conspiracy. More surprising still was the target of this assassination scheme, syndicated columnist Jack Anderson, then the most famous investigative reporter in the United States, whose exposés had plagued President Richard Nixon since he had first entered politics more than two decades earlier. Most astonishing of all, the men who plotted to execute the journalist were covert Nixon operatives dispatched after the President himself darkly informed aides that Anderson was “a thorn in [his] side” and that “we’ve got to do something with this son of a bitch.”

The conspirators included former agents of the FBI and CIA who had been trained in a variety of clandestine techniques, including assassinations, and who would later go to prison for their notorious break-in at Democratic Party headquarters in the Watergate building. According to their own testimony, the men weighed various methods of eliminating the columnist: by spiking one of his drinks or his aspirin bottle with a special poison that would go undetected in an autopsy, or by putting LSD on his steering wheel so that he would absorb it through his skin while driving and die in a hallucination-crazed auto crash.

In one sense, the White House plot to poison a newsman was unprecedented. Certainly no other president in American history had ever been suspected of ordering a Mafia-style hit to silence a journalistic critic. Yet it was also an extreme and literal example of a larger conspiracy to contaminate the rest of the media as well, a metaphor for what would become a generation of toxic conflict between the press and the politicians they covered. It was not just that Nixon’s administration wiretapped journalists, put them on enemies lists, audited their tax returns, censored their newspapers, and moved to revoke their broadcasting licenses. It was, more lastingly, that Nixon and his staff pioneered the modern White House propaganda machine, using mass-market advertising techniques to manipulate its message in ways that all subsequent administrations would be forced to emulate. Nixon simultaneously introduced the notion of liberal media bias even as he launched a host of spinmeisters who assembled a network of conservative news outlets that would drive the political agenda into the twenty-first century. At the same time, Nixon and subsequent presidents effectively bought off news corporations by deregulating them, allowing them to gorge themselves on a noxious diet of sensationalism and trivialities that reaped record profits while debasing public discourse.

How did all of this come to pass? In many ways, the rise of Washington’s modern scandal culture began with Richard Nixon and Jack Anderson, and their blistering twenty-five-year battle symbolized and accelerated the growing conflict between the presidency and the press in the Cold War era. This bitter struggle between the most embattled politician and reviled investigative reporter of their time would lead to bribery and blackmail, forgery and burglary, sexual smears and secret surveillance—as well as the assassination plot. Their story reveals not only how one president sabotaged the press, but also how this rancorous relationship continues to the present day. It was Richard Nixon’s ultimate revenge.

It was this very lust for revenge—Nixon’s obsession with enemies—that would destroy him in the end. In the President’s eyes, his antagonists in what he called the “Eastern establishment” were legion: liberals, activists, intellectuals, members of Congress, the federal bureaucracy. But none was more roundly despised than the news media, and none in the media more than Jack Anderson, a bulldog of a reporter who pounded out his blunt accusations on the green keys of an old brown manual typewriter in an office three blocks from the White House. Although largely forgotten today, Anderson was once the most widely read and feared newsman in the United States, a self-proclaimed Paul Revere of journalism with a confrontational style that matched his beefy physique. Part freedom fighter, part carnival huckster, part righteous rogue, the flamboyant columnist was the last descendant of the crusading muckrakers of the early twentieth century. He held their lonely banner aloft in the conformist decades afterward, when deference to authority characterized American journalism and politics alike.

At his peak, Anderson reached an audience approaching seventy million people—nearly the entire voting populace—in radio and television broadcasts, magazines, newsletters, books, and speeches. But it was his d

aily 750-word exposé, the “Washington Merry-Go-Round,” that was the primary source of his power; published in nearly one thousand newspapers, it became the longest-running and most popular syndicated column in the nation. Anderson’s exposés—acquired by eavesdropping, rifling through garbage, and swiping classified documents—sent politicians to prison and led targets to commit suicide. He epitomized everything that Richard Nixon abhorred.

The President had always believed the press was out to get him, and in Anderson he found confirmation of his deepest anxieties. The newsman had a hand in virtually every key slash-and-burn attack on Nixon during his career, from the young congressman’s earliest Red-baiting in the 1940s to his financial impropriety in the White House during the 1970s. Even Nixon’s most intimate psychiatric secrets were fodder for Anderson’s column. The battle between the two men lasted a generation, triggered by differences of politics and personality, centered on the most inflammatory Washington scandals of their era. In the beginning, Anderson’s relentless reporting helped plant the first seeds of Nixonian press paranoia. In the end, Anderson’s disclosures led to criminal convictions of senior presidential advisors and portions of articles of impeachment against the Chief Executive himself. The columnist both exposed and fueled the worst abuses of the Nixon White House, which eventually reached their apogee in the Watergate scandal that ended his presidency in disgrace.

Surprisingly, the story of the Nixon-Anderson blood feud is little known, in part because the muckraker’s checkered reputation made him an unsympathetic hero to contemporaries and in part because he was overshadowed by other reporters during the Watergate scandal. In addition, the Nixon cover-up continues even from the grave, as his estate and federal agencies block access to many historical records. Still, a wealth of fresh material—oral history interviews, once-classified government documents, and previously secret White House tape recordings—shed new light on this fascinating tale of intrigue.

The struggle between Nixon and Anderson personified a larger story of political scandal in the nation’s capital during the decades after World War II and involved a virtual Who’s Who of Washington’s most powerful players: Joseph McCarthy, J. Edgar Hoover, Martin Luther King, George Wallace, Henry Kissinger, Ronald Reagan, and all three Kennedy brothers, John, Robert, and Teddy. Anderson’s vilification of Nixon, a blend of courageous reporting and cheap shots, focused on his private as well as his public life and helped usher in what another beleaguered president, Bill Clinton, would call “the politics of personal destruction.” It was a supreme irony that Nixon triggered a renaissance of the very investigative reporting he so passionately reviled, and it turned out to be one of his most lasting legacies.

In turn, the President’s fierce campaign against Anderson proved to be the forerunner of the modern White House political attack machine. Not only did Nixon set the combative tone that would resonate in the “war rooms” of future election campaigns and administrations, he also helped launch the careers of many powerful personalities—Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, Patrick Buchanan, Karl Rove, Roger Ailes, Lucianne Goldberg—who would achieve notoriety for their own abilities to manipulate the media on behalf of Nixon’s presidential successors. While Anderson’s tireless muckraking of Nixon was exceptional, the vitriol it spawned would become standard fare in the nation’s capital for the next generation.

To be sure, Anderson was just one in a legion of Nixonian enemies, just as Nixon was only one of Anderson’s many antagonists; in no sense was the relationship between the President and the columnist one of equals. It is not surprising that the two men had only a handful of face-to-face encounters over the years: Nixon kept his distance from most reporters, even sympathetic ones, and Anderson rarely spent much time with his prey. Still, “as a target of ugly thoughts,” the President’s legal counsel said, the investigative columnist eclipsed all of Nixon’s other adversaries. “At the White House,” another senior advisor recalled, “we considered him our arch nemesis.”

For a variety of reasons, Anderson posed the greatest threat of any newsman: because he was willing to publish derogatory information that more mainstream journalists eschewed; because his syndicated column allowed independence from censorship by any single editor or publisher; and because he was unencumbered by any pretense of objectivity. Indeed, Anderson unabashedly thrust himself into the fray, gleefully passing out classified documents to other reporters and righteously testifying before congressional committees and grand juries that would invariably be convened in the wake of his disclosures. In the secret office of Nixon’s White House operatives, Anderson’s name was posted on the wall as a kind of public enemy number one, inspiring them against their foe. According to one presidential aide, Nixon’s enmity was so great that “he will fight, bleed and die before he will admit to Jack Anderson that he’s wrong or that he’s made a mistake.”

The warfare between the two was intermittent, punctuated by an occasional truce born of expediency or exhaustion or some greater enemy looming temporarily on the horizon. With each attack came a counterattack, until it became nearly impossible to determine who struck first or who was really at fault. While Anderson hounded Nixon in the full glare of the media spotlight, the President’s assaults were launched in secret and designed to remain hidden.

In their determination to vanquish each other—and in their larger quest for power—Nixon and Anderson did not hesitate to use ruthless tactics. The President’s transgressions, of course, were criminal, and included obstruction of justice by paying hush money to cover up the Watergate break-in, and other acts of political sabotage and abuse of power. Anderson’s infractions were less infamous but also glaring. Years before Watergate, he was linked to bugging and break-ins, and he came perilously close to exposure for bribery and extortion of his news sources. Both men rationalized their duplicitous means in the belief that their ultimate ends were pure. Neither seemed to appreciate the inherent moral contradiction in what they did, or the similarities between their own calculating opportunism. Although both were propelled by a sense of personal virtue, they would be remembered above all for their dirty tricks.

In the end, Nixon and Anderson both learned the hard way the true, coarse price of power, brazenly grasped through fleeting alliances of convenience and a myriad of compromises great and small. “Few reach the political pinnacles without selling what they do not own and promising what is not theirs to give,” Anderson wrote, for “it is easy to forget that power belongs not to those who possess it for the moment, but to the nation and its people.” Yet this was as true for journalists like Jack Anderson as it was for politicians like Richard Nixon. In utterly different ways, these utterly different men both played crucial parts in poisoning government and the press.

Of course, predatory politics did not begin with Richard Nixon, and America’s scandal-obsessed media long predates Jack Anderson. In the earliest days of the Republic, vilification of the press was standard fare. The normally controlled George Washington was “much inflamed” by the “personal abuse which had been bestowed on him” by journalists, said his secretary of state, Thomas Jefferson; the first president was enraged when newspapers published confidential Cabinet minutes, which may have been leaked by Jefferson himself in an effort to influence administration policy. Through the press, Jefferson supporters also exposed a sex scandal involving his rival, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, a character assassination that became quite literal when it culminated in Hamilton’s fatal duel with Jefferson’s vice president, Aaron Burr. But using the media as an instrument of political warfare worked both ways, and venomous editors savaged Jefferson with equal bile; one newspaper claimed that the Chief Executive kept “as his concubine, one of his slaves” and with “this wench Sally, our president has had several children.” It would be nearly two centuries before DNA testing corroborated this sexposé, which lived on for posterity thanks to the free press that Jefferson championed. No wonder the father of the First Amendment ultimately lamented “the

putrid state into which our newspapers have passed.”

In Jefferson’s time, most publications were funded not by advertising, as they are today, but by political parties, which used the press as a weapon of propaganda. In the nation’s capital, favored printers received lucrative federal contracts to transcribe congressional debates, making Washington journalism an unsavory blend of stenography and partisanship that has persisted to the present. Still, as media outlets evolved from party organs to profit-making businesses, the most vicious forms of journalistic invective began to fade away. The commercialization of news led papers to try to maximize circulation and avoid alienating readers by not choosing sides between one party or the other. Politicians and the press formed symbiotic relationships, linked by professional and financial self-interest; many Washington reporters secretly moonlighted on the side for officials they covered. Journalistic and governmental corruption became particularly rampant in the late nineteenth century, when the soaring profits of the industrial revolution led politicians to sell their votes and reporters to prostitute their pens to the highest bidder. When the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Washington bureau chief uncovered massive bribery of members of Congress, for example, instead of exposing the corruption he extorted payoffs to cover it up. Other newsmen used their connections to arrange federal appointments or leak inside information to financial speculators in exchange for bribes.

By the early twentieth century, the most flagrant corruptions of politics and press had ceased, but generally each still found cooperation more advantageous than conflict. Gentlemen reporters politely vied to be called upon at presidential news conferences and socialized after hours with Washington’s ruling class. The vituperation that characterized coverage in the early years of the Republic largely disappeared.

Poisoning The Press

Poisoning The Press